Venus: Earth’s Neighbour, But Not Its Twin

Earth is often described as an ocean world, with water covering 71% of its surface. Venus, our closest planetary neighbour, shares a similar size and rocky composition, earning it the nickname “Earth’s twin.” However, despite these similarities, new research suggests Venus never had oceans.

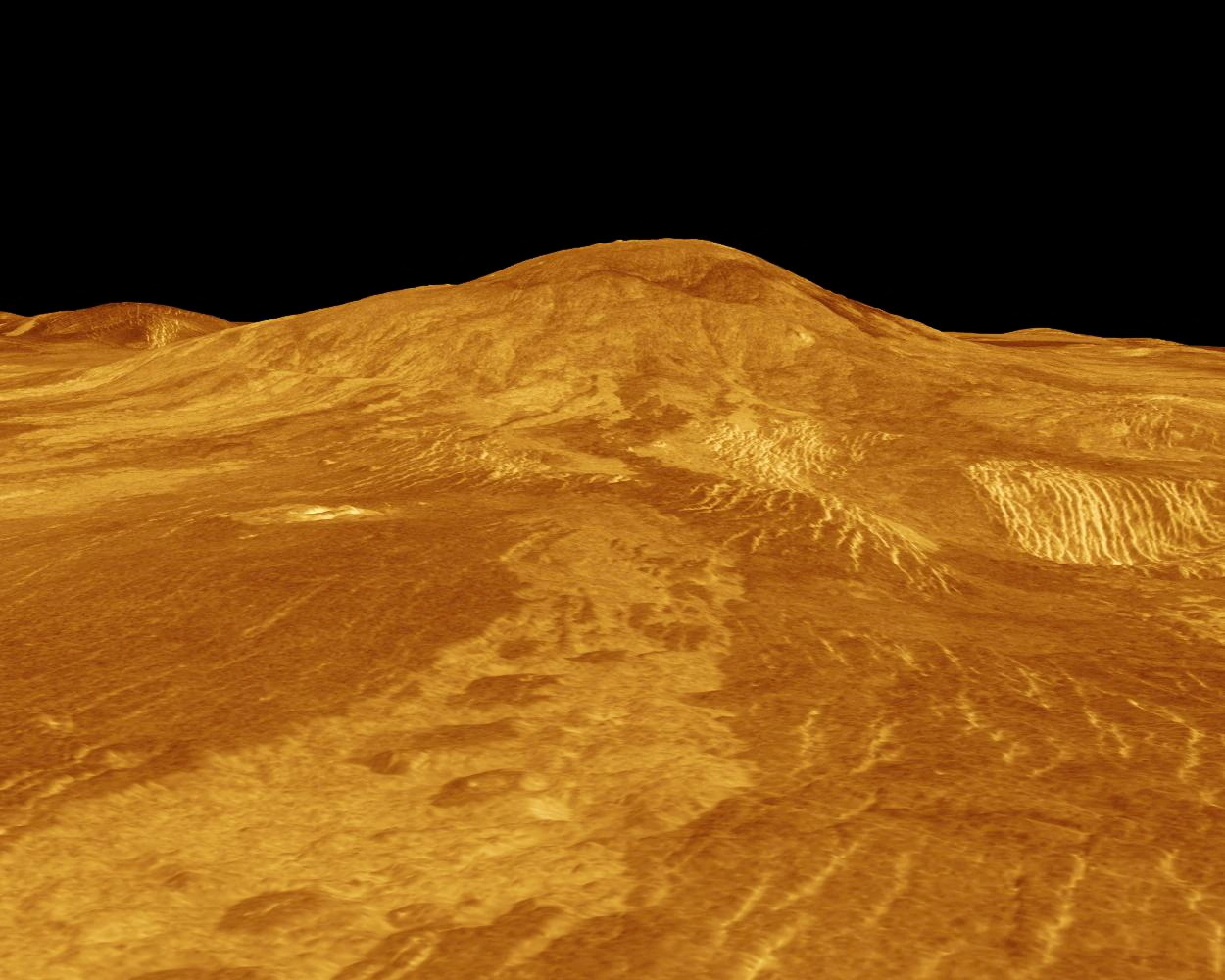

Scientists have studied the chemical composition of Venus’s atmosphere to infer the water content of its interior. Their findings indicate that Venus’s interior is substantially dry. This desiccated state likely stems from its early history when its surface was dominated by molten rock, leaving no room for the development of oceans.

Why Venus Lacked Water

Water is essential for life, making the study’s conclusions about Venus particularly significant. Researchers determined that volcanic eruptions on the planet release only 6% water vapour, compared to over 60% water vapour released during volcanic activity on Earth. This minimal water vapour points to a dry interior and supports the idea that Venus’s surface was parched from its inception.

According to lead author Tereza Constantinou, of the University of Cambridge, a water-rich Venus would imply a habitable past. Instead, the study shows Venus likely remained dry throughout its history, never experiencing conditions suitable for life.

Venus’s Uninhabitable Present

Venus is the second planet from the Sun, with extreme conditions that starkly contrast Earth’s. Its atmospheric pressure is 90 times that of Earth, surface temperatures soar to 465°C (869°F), and its atmosphere is laden with toxic clouds of sulfuric acid. These factors make it one of the least hospitable places in our solar system.

Unlike Mars, which shows signs of past oceans and possibly even deep reservoirs of liquid water today, Venus has no such surface features. Evidence suggests the planet’s evolution diverged sharply from Earth’s.

Future Explorations of Venus

Despite limited studies compared to Mars, future missions aim to deepen our understanding of the planet. NASA’s DAVINCI mission, planned for the 2030s, will explore Venus’s atmosphere and surface using flybys and a descent probe. Similarly, the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission will conduct radar mapping and atmospheric analysis during the same decade.

Tereza Constantinou highlights Venus as a key to studying planetary habitability. She says, “The planet provides a natural laboratory for studying how habitability—or the lack of it—evolves.”

With inputs from Reuters