One must sincerely appreciate the Australian Space Agency’s (ASA) straightforwardness in calling a spade a spade. They are not feeling unnecessarily coy by pretending to be a civilian space agency with no instrumentality to take formal stances in the nation’s interest. A relatively new space agency, the ASA is assertive of its stance on global interests and its penchant for being a global ‘space situational awareness’ (SSA) police. ASA’s social media operators have made their purpose very clear, unlike those intellectually deficient social media managers of ISRO, who are childishly happy making some ‘jealous’ by sharing new Chandrayaan pictures.

Australia is deeply invested in space situational awareness and in shaping global policies around it. This is evident from the Australian Civil Space Strategy 2019-2028, which has prioritised Space Situational Awareness and Debris Monitoring. The Civil Space Strategy comes up on four strategic pillars – inspiring and improving the lives of Australians, developing Australian capabilities in areas of competitive advantage, opening doors internationally, and addressing safety and national interests. The Civil Space Strategy also has identified four priority areas – access to space, automation and robotics, leapfrog R&D, and space situational awareness and debris monitoring. Canberra has economic goals from these four pillars and priority areas. By 2030, it intends to generate a national space economy of around 12 billion dollars and jobs for over 20000 skilled personnel.

As a subset of much wide-aspect Space Domain Awareness, SSA also prominently features in the Australian Department of Defence’s “Australia’s Defence Space Strategy” document. This document is quite frank. It begins with acknowledging that Australia is too dependent on its allied and international partners for its space access, data, command and control, and force projection. The same document also attributes the dependency to shared capabilities, especially between the Combined Space Operations (CSOp) Initiative partners, including the US, UK, New Zealand, Canada, Germany, and France. Together, these countries have formulated the Combined Space Operations Vision 2031 document. The document is interesting, particularly if one considers those recent posts from ASA’s social media handle about the purported Polar Synchronous Launch Vehicle’s (PSLV) expended stage debris that came on shore in Western Australia.

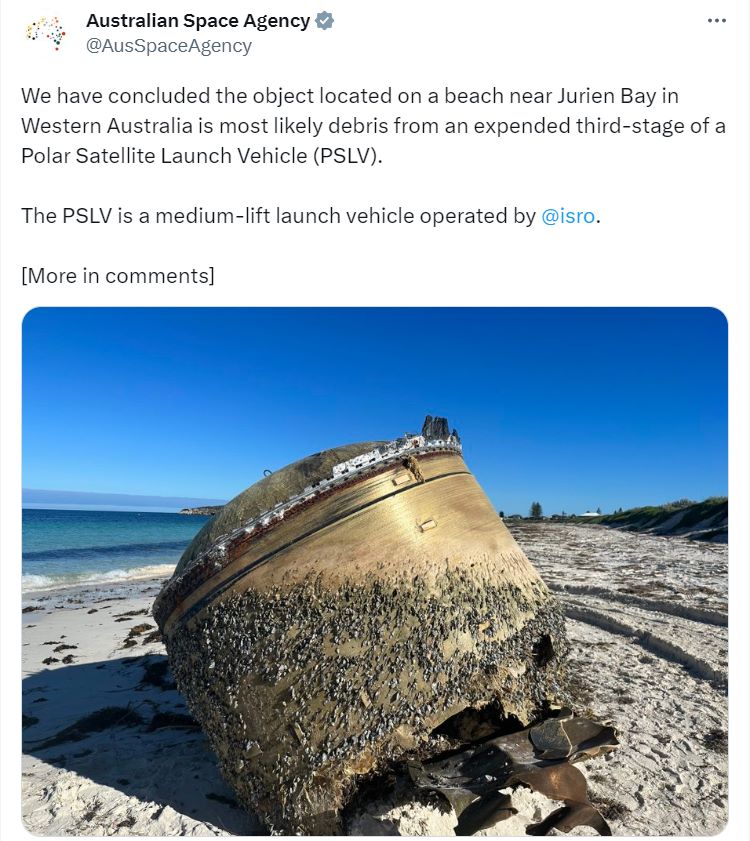

The tweet thread went somewhat in this manner. ASA mentions that the debris is likely from the expended third stage of India’s PSLV, operated by the Indian Space Research Organization. Tweet number two. The debris is in ASA’s custody, and it is interacting with ISRO on its confirmation and determining the following steps, which also include ‘obligations’ under UN space treaties. The last tweet says that ASA is committed to debris mitigation and will continue highlighting it internationally.

Let us summarise this for our foreign and space policymakers in New Delhi to comprehend. The exercise of having two sets of space agencies – civilian and military – is to have a soft- and hard-power entrapment to achieve national goals. Where pushing for space sustainability and invoking responsible behaviour are ‘softer’ facets of ensuring pliability, denying access, stringently invoking malleable international laws, and creating international pressure are more hard-power tactics. It is a bit difficult to gulp, but the fact remains that despite the India-Australia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, Canberra while tweeting, appeared more as a fervent AUKUS partner.

Australia’s stakes in the AUKUS partnership are asymmetrically low. This case is also presented by Australian professor and former intelligence officer Clinton Fernandes in his book – ‘Subimperial Power: Australia in the International Arena’. Not to forget the awkward cancellation of the French Naval Group’s Attack-class of submarines by the Royal Australian Navy, a contract that later went to UK’s BAE Systems. In Australia’s strategic play, and among all the multilaterals it is in, the AUKUS stands superior to Five Eyes or even Quad. This would also reflect in its space strategy. The irony for Canberra is that the same AUKUS is likely also responsible for its high technology reliance and, therefore, the techno-political dependency that the Australian Defence Space Strategy document acknowledges. A recent survey in Australia, done with American cognisance, shows that one in five tech graduates in Australia works for American tech companies.

As for the PSLV debris, here is the fact. Although unconfirmed today, let’s assume Canberra correctly recognises it as a PSLV expended debris. Did this part make a kinetic impact on Australia – the answer is no. As the publicised image shows, the piece has numerous barnacles and an algal biofilm, suggesting it has been on the sea for many months before appearing on shore. Also, we must consider that the Indian Ocean gyre – oceanic current – flows very close to the beaches of Western Australia. So if it is a PSLV part, it may have dropped into the waters close to India’s eastern shores, and the gyre could have carried it over months.

About the sustainability narrative. The world is poised to encourage increased use of reusable launchers, but if anyone is to be made an example, that would be those nations who have launched the most. Has any country invoked the Liability Convention for expended launch vehicle parts of space-faring nations that came to their shores? Gradually, India is making headways into reusable launchers, and the first demonstration may happen anytime in the next ten years. But then Australia singularly isolating India, and making a case out of a strategic partner, only to further a sustainability narrative, is the last thing one would do to a nicely progressing space partnership. India continues to perform excellently in space debris mitigation aspects. Last month, while launching several Singaporean satellites on a PSLV fleet, ISRO ensured that the fourth stage was reduced in altitude and would eventually spend considerably less time in the Earth’s orbit.

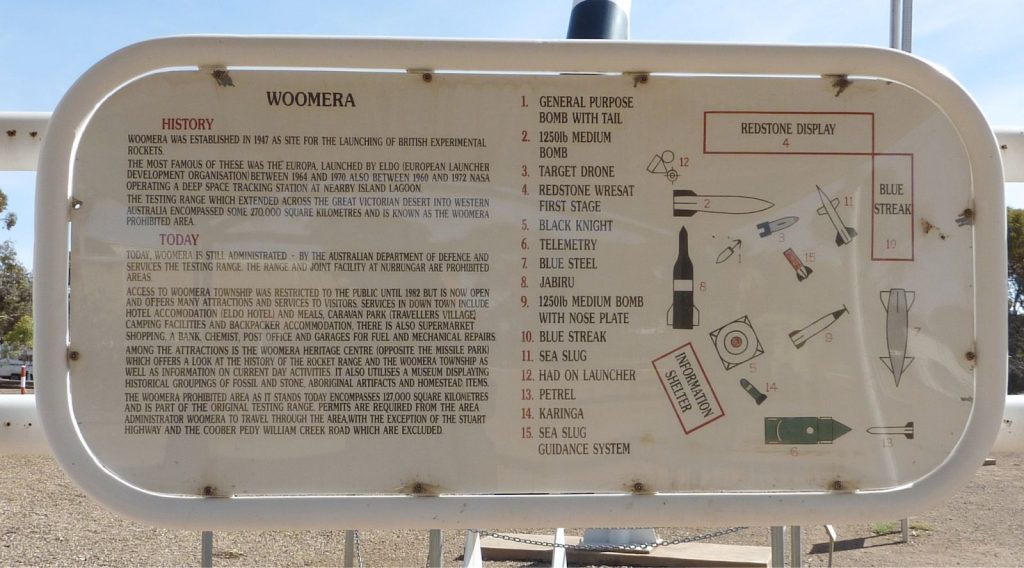

Among the space-capable nations, India has a small debris footprint here on Earth or in the orbits. The PSLV has hardly seen 58 launches, and India has at most 100 satellites orbiting. PSLV is not the only expendable rocket in the world that sheds its stages into the oceans; almost every rocket launched in modern history has shed its stages in the waters. The entire reason for Vandenberg Air Force Base, Cape Canaveral, Tanegashima, Kourou and Sriharikota to be on the coast is that the expended parts should not fall on land. The question to Canberra is, would it invoke the same space treaties to the US if parts of the thousands of rockets the latter launched to this day land on its shores after years adrift in the oceans? Would Canberra look into its backyard where expended parts of the British Blue Streak missile and launch vehicle, launched from Woomera in the 1960s, have littered the desolate regions of Queensland and Northern Territory?

Space launches have never been squeaky clean acts for the multi-stage and expendable technology the world adopted during the First Space Age. With growing emphasis on recallable stages and environmentally friendlier fuels, launching will get cleaner sooner or later. The Indian space program will positively contribute to it. India and Australia could make it a cooperation agenda of their strategic dialogue. ASA, which is highly dependent on the US for its space access, is justified in demanding that India comply with outer space treaties. It has all the eyes in space, given its penchant for space situational awareness and the geographical advantage it enjoys to ensure the same proclivity. How soon it sets the same stringent bar for its AUKUS partners, the UK and the US, should be seen.