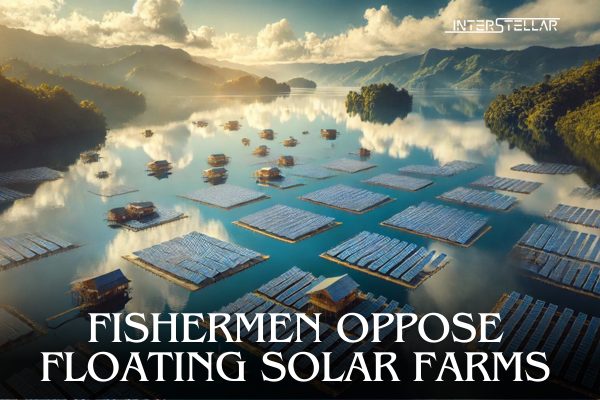

Fishermen in the Philippines Resist Floating Solar Farms on Laguna de Bay

For the past 40 years, fishing has been the primary livelihood for Alejandro Alcones. However, he now faces the potential replacement of his small boat with a floating solar farm on the Philippines’ largest lake. The government’s plan to install solar panels on Laguna de Bay, a critical source of freshwater fish, has sparked concern among local fishermen who fear for their livelihoods.

The Lifeline of Laguna de Bay

Laguna de Bay, which spans 91,000 hectares southeast of Manila, is not just a lake; it is a lifeline for many. Alcones, a 55-year-old fisherman, is among the 13,000 people who depend on the lake for their income. “Laguna Lake gives life and income to fishermen like us who didn’t finish school. It also gives many displaced workers here an alternative way to earn by fishing,” says Alcones, who supports his family by fishing in the lake.

However, the government’s push for renewable energy is set to change this. The Philippines, an archipelago of more than 7,000 islands, faces significant land constraints as it strives to meet its goal of generating 50% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2040. Floating solar farms, which can be placed on reservoirs, ponds, and offshore waters, offer a solution for countries like the Philippines that have limited land and high population density.

Concerns Over Floating Solar Farms

The Laguna de Bay project is seen as a pioneering effort, as it aims to be the world’s first large-scale floating solar farm on a natural lake. The project plans to cover 2,000 hectares of the lake with solar panels, generating about 2 gigawatts of electricity by 2026. While this initiative could power millions of homes, it has raised concerns among local communities, particularly fishermen.

According to the Laguna Lake Development Authority (LLDA), the state agency overseeing the project, consultations with local fishermen have been ongoing. However, the National Federation of Small Fisherfolk Organizations in the Philippines, or Pamalakaya, argues that the consultations have been insufficient. Pamalakaya, representing more than 8,000 fishermen and aquaculture workers, fears the project will further reduce fishing grounds, already diminished by previous developments.

Ronnel Arambulo, Pamalakaya’s vice chairperson, highlights potential hazards such as floating panels becoming untethered during typhoons, damaging boats and docks, and further shrinking fishing grounds. “We are worried that the floating solar farms will further shrink our fishing grounds that have already been reduced by past development projects,” Arambulo said.

The concerns extend beyond just the fishermen. A report by the Responsible Energy Initiative warns of potential environmental risks associated with floating solar farms, including coastal soil erosion, disruption of photosynthesis, and decreased fish yields due to ecosystem changes.

Balancing Renewable Energy and Local Livelihoods

Despite these concerns, the government remains committed to the project, emphasising the need to transition to renewable energy. The Philippines currently relies heavily on coal, with 62% of its electricity production coming from this fossil fuel. Floating solar farms are seen as a way to expand renewable energy without competing with agriculture for land.

Mylene Capongcol, Assistant Secretary at the Department of Energy, supports the development of floating solar projects, viewing them as essential for achieving the country’s renewable energy targets. “The Department of Energy supports the development of floating solar projects as this will contribute to the government’s target of a 35% renewable energy share in the power generation mix by 2030 and 50% by 2040,” she said.

However, as the country races to meet these targets, it faces the challenge of balancing energy needs with the livelihoods of local communities. Marvin Lagonera, an energy transition strategist for Southeast Asia, advocates for a rights-based approach in clean energy transitions. He stresses the importance of engaging impacted communities, including civil society and environmental groups, to ensure that projects like the Laguna Lake solar farm are both ecologically safe and socially just.

The LLDA believes that the floating solar farms could eventually benefit the local fisheries. According to Mhai Dizon, the LLDA’s renewable energy project coordinator, studies suggest that the underside of the solar panels could serve as breeding grounds for fish. However, this potential benefit is met with scepticism by many fishermen, who fear the loss of their traditional livelihoods.

Conclusion

As the government moves forward with the Laguna de Bay project, the voices of those like Alcones and Arambulo highlight the need for careful consideration of the human and environmental impacts of renewable energy developments. While the transition to renewable energy is critical, it must be achieved in a way that does not compromise the livelihoods of those who depend on the land and water for their survival.